Diminishing returns : On India and its Shanghai Cooperation Organisation engagement

India benefitted as a member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, but the future is not bright

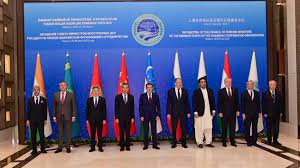

The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation-Council of Heads of State meeting, hosted by Prime Minister Narendra Modi on Tuesday, marked the first time India chaired the summit of regional countries. India became a full SCO member in 2017, along with Pakistan. The government has held that joining the originally Eurasian group was important as member-countries make up a third of the global GDP, a fifth of global trade, a fifth of global oil reserves and about 44% of natural gas reserves. Also important is its focus on regional security and connectivity — areas key to India’s growth and making up its challenges, such as terrorism in Pakistan, and Chinese aggressions as well as the Belt and Road Initiative. Being “inside the tent” is important, especially as Pakistan is a member, even if that means conducting joint exercises under the SCO Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure. The SCO also gives India an interface with Central Asian markets and resources. Finally, joining the SCO was a key part of India’s stated ambitions on “ multi-alignment ” and “ strategic autonomy” while becoming a “balancing power” in the world, and it seems no coincidence that the Modi government joined the revived Quad with the U.S., Japan and Australia in the same year that it took up the full SCO membership. Over the past year, this has become an economic necessity as India has chosen to be neutral on the Ukraine war, benefiting from fuel and fertilizer purchases from Russia.

Therefore, it was expected that India’s turn to chair the SCO this year would be a major event, rivalling the expected pomp around the G-20 meet in September. In addition, given Russia’s and China’s blocks on the G-20 joint communiqué that India is keen to find consensus on, the SCO summit would have been a convenient venue for Mr. Modi to negotiate a resolution with his counterparts. However, India’s decision to postpone the SCO summit due to the Prime Minister’s U.S. State visit, and then to turn it into a virtual summit may have been a dampener on the SCO outcomes. India’s concerns with hosting Xi Jinping given the LAC hostilities, or Pakistan Prime Minister Sharif’s possible ‘ grandstanding ’, or even the optics of welcoming Russian President Vladimir Putin may have been factors. Whatever the reason, while the members hammered out a New Delhi declaration and joint statements on radicalisation and digital transformation, the government was unable to forge consensus on other agreements including one on making English a formal SCO language, while India, despite being Chair, did not endorse a road map on economic cooperation, presumably due to concerns over China’s imprint. With its SCO chairpersonship ending, the government may now be feeling the law of diminishing returns over its SCO engagement — one that might make its task of hosting the G-20 even more difficult.