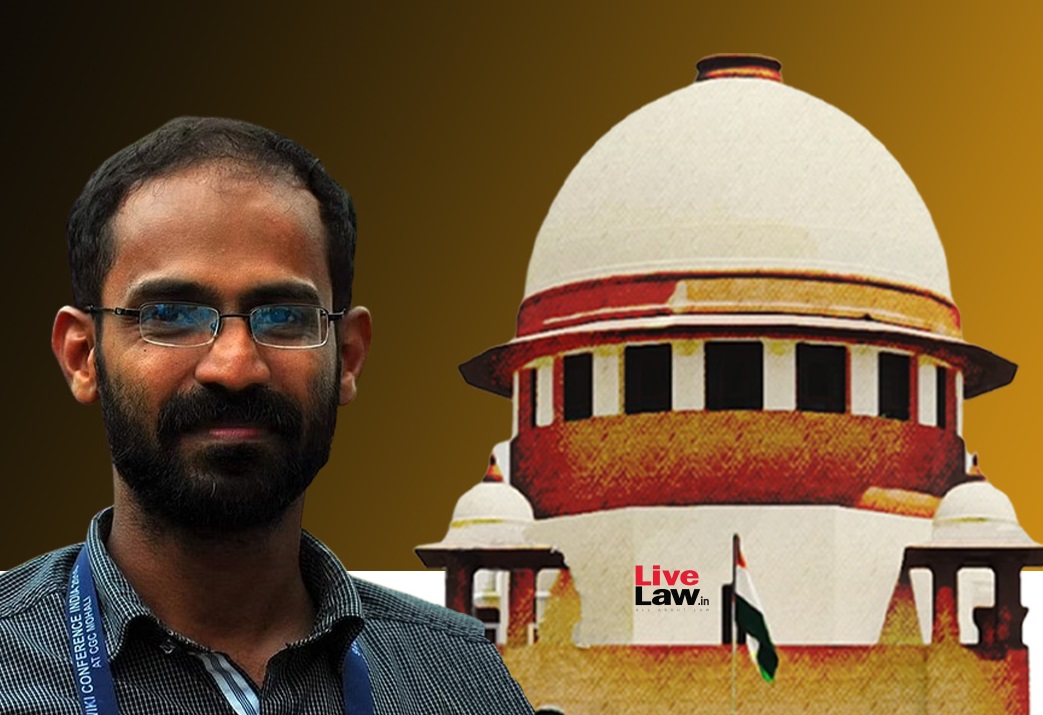

Relief, at last : On bail to journalist Siddique Kappan

The Supreme Court has exposed the tenuous nature of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act case against journalist Kappan

Even for a system in which foisting of false cases is not uncommon, the prolonged imprisonment of journalist Siddique Kappan in Uttar Pradesh was quite an egregiously malevolent instance. In directing his release on bail, subject to conditions that are not onerous, the Supreme Court has rightly bypassed the bail-denying feature of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act by posing pertinent questions and concluding that there was no reason for keeping him in custody any further. Mr. Kappan was arrested in October 2020 while he was on his way to Hathras, where a Dalit girl had been gang-raped and murdered. In a baffling move that could only be explained as an attempt to divert attention from the public outcry caused by the incident and float a conspiracy theory with communal overtones, he was charged with plotting a divisive campaign in the area. And to ensure that he was kept in prison for a long time, the police invoked provisions of the anti-terror law — ones that related to raising funds for a terrorist act and a conspiracy to commit it — besides penal provisions concerning promoting enmity between communities and outraging religious feelings. He was described as a member of the Popular Front of India. Pamphlets calling for justice for the victim and literature in English (which turned out to be instructions given in English for use in the ‘Black Lives Matter’ protests in the United States), were cited as material to implicate him.

It is to the credit of the Bench under the Chief Justice of India, Justice U.U. Lalit, that it did not go by the usual penchant for citing Section 43D(5) of the UAPA to deny bail. The provision contains a legal bar on granting bail if the Court is of the opinion that there are reasonable grounds to believe that the accusation against those held is prima facie true. A 2019 judgment forbids a detailed analysis of the evidence at the bail stage. However, a common-sense approach to the facts of a case may lead to a better appreciation of the question of bail. By orally asking how raising one’s voice in support of justice for a victim would amount to a crime and wondering why a person planning to foment communal violence would use pamphlets in English written for a protest in another country, the Bench proved the shaky foundations of the whole case. The bail order demonstrates how a clear-headed approach can help judges relieve officials and political leaders of their smug belief that by invoking anti-terror laws, they can keep disfavoured accused in prison for long years without any basis. At the same time, it reflects poorly on the judiciary that it took two years for the courts to grant liberty to Siddique Kappan. One should hope that this order will send a message down the judicial hierarchy on how courts should not allow the police to persecute people through stringent laws.