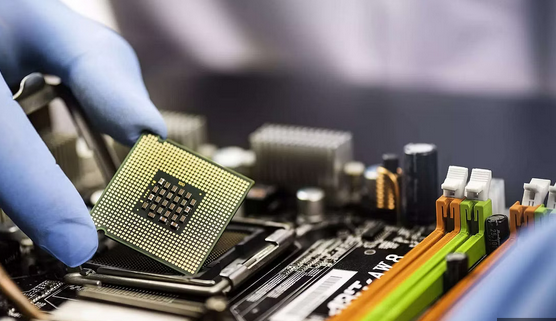

Chip off the blocks : On semiconductor fabrication in India

As incentives for semiconductors sputter , course corrections are due

As funds for production-linked incentives (PLI) for manufacturing semiconductors lie under-utilised by upwards of 80%, the Union government must be far clearer on what it has achieved — and aims to accomplish — by continuing to spend crores of rupees on bringing more semiconductor fabrication capabilities to India. While the PLI scheme for IT hardware has a ₹17,000 crore outlay , the one for semiconductors and displays has ₹38,601 crore earmarked . On the employment and substantive value addition fronts , existing schemes in and of themselves show little promise: while chips are important for most hardware and appliances, making them employs advanced and automated systems, and manufacturing facilities employ few people for the value generated in sales. Not all big-ticket spending in the national interest translates into domestic employment, as import-heavy defence spending shows. But the central wager with these schemes, at much cost to the exchequer , lies in attracting an “ecosystem” that will increase the value addition of India’s electronics manufacturing sector. This is far from a guaranteed outcome, even if PLI benefits are availed optimally . The wager also relies on global manufacturing giants giving other benefits of a globally distributed supply chain a go-by , including cheap and accessible international transport facilities for chips.

The constellation of PLI schemes remains a wager nonetheless . And it must be bolstered by other efforts to strengthen India’s hand — encouraging semiconductor design talent to develop domestically. Some efforts here, such as the design-linked incentive scheme, show promise. But the bulk of the capital remains focused on the assembly and subsidising of large manufacturing plants, with much of the raw and even intermediate material still being imported. And with the limited scope of what the PLI funds are incentivising, multinational chipmakers are staying away from making substantive commitments , despite incentives. Private capital is also in a state of flux , with advancements in chips and emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence leaving policymakers guessing on how best to allocate resources to boost their technological position for the coming decade . These outlays must, therefore, be pegged to a tangible outcome: is this a matter of safeguarding cyber sovereignty to protect India from another pandemic-style supply chain shock, encouraging the domestic electronics industry to make electronics cheaper for Indian consumers, or asserting India as a global electronics manufacturing centre? Clarity on desired outcomes would make failures easier to spot. It would also make it possible to course correct before massive PLI spending has already taken place with little to show for the outflow.