Revision sans vision: On the three Bills that replace the body of criminal laws in India

New laws have positive features, but bring no path-breaking change in system

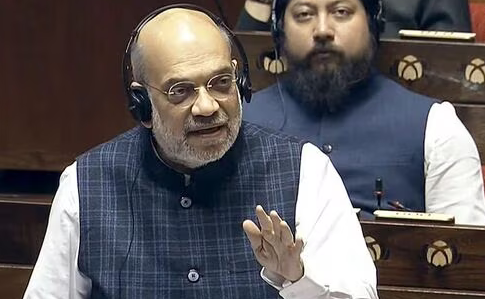

Law-making in the absence of a significant number of Opposition members does not reflect well on the legislature . The three Bills that replace the body of criminal laws in India were passed by Parliament in its ongoing session in the absence of more than 140 members. Even though the revised versions of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS, which will replace the IPC), the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (which will replace the CrPC) and the Bharatiya Sakshya Bill (instead of the Evidence Act) were introduced after scrutiny by a Parliamentary Standing Committee, they still required legislative deliberations in the full chambers , given their implications for the entire country. Many concerns that the Bills gave rise-to could not be raised in Parliament as a-result . A conspicuous aspect of the new codes is that barring reordering of the sections, much of the language and contents of the original laws have been retained. However, Union Home Minister Amit Shah’s claim that the colonial imprint of the IPC, CrPC and the Evidence Act has been replaced by a purely Indian legal framework may not be correct, as the new codes do not envisage any path-breaking change in the way the country is policed , crimes are investigated and protracted trials are conducted.

The improvements in the BNS include the removal of the outdated sedition section, as exciting disaffection against the government or bringing it into hatred and contempt is no more an offence, and the introduction of mob lynching (including hate crimes such as causing death or grievous hurt on the ground of a person’s race, caste, community, sex, language or place of birth) as a separate offence. Another positive feature is the government ignoring the panel’s recommendation to bring back adultery , struck down by the Supreme Court, as a gender-neutral offence. However, it is questionable whether ‘terrorism’ should have been included in the general penal law when it is punishable under special legislation. Grave charges such as terrorism should not be lightly invoked . On the procedural side, some welcome features are the provision for FIRs to be registered by a police officer irrespective of where an offence took-place and the boost sought to be given to use of forensics in investigation and videography of searches and seizures . A significant failure lies in not clarifying whether the new criminal procedure allows police custody beyond the 15-day limit, or it is just a provision that allows the 15-day period to spread across any days within the first 40 or 60 days of a person’s arrest. Revisions in law cannot be made without a vision for a legal framework that addresses all the inadequacies of the criminal justice system.