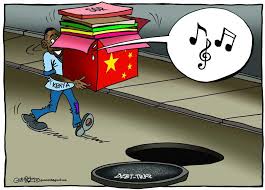

Debt trap : On crisis in Kenya

Kenya must find ways to service its debt without punishing its people

The Kenyan President’s decision to rush through Parliament an IMF-backed finance Bill that sought to increase taxes on everything from imported sanitary pads and tyres to bread and fuel backfired, with protesters storming a section of the Parliament on Tuesday. After the protests, which rights groups said had left at least 23 people killed and 200 injured, President William Ruto announced that he would not sign the Bill. The Kenyan government could have avoided this bloody confrontation had it paid more attention to the public mood. The government’s plan was to raise an extra 200 billion Kenyan shilling (some $1.55 billion) in taxes. Earlier this year, the country had reached a deal with the IMF to secure $941 million in additional lending. In subsequent talks in Nairobi, they agreed to reforms, including tax increases, to stabilise the country’s debt-battered financial situation. The IMF deal triggered street protests. But the government still went ahead with the plan to impose additional taxes on the country of 54 million people, a third of whom still live in poverty.

The government argues that its hands were tied as the country struggles to repay its huge debt burden — domestic and foreign debt was a staggering $80 billion last year, accounting for nearly three-fourths of its GDP. The government spent more than half of its revenue servicing debts last year. The crisis is an indictment of the development model Kenya and several other countries in the continent follow. Kenya, one of the fastest growing countries in Africa, has borrowed heavily from multinational lenders such as the World Bank and the IMF as well as bilateral partners such as China, to finance its infrastructure projects. But growth tanked and expenses rocketed during the COVID-19 pandemic years. The Ukraine war has led to a spike in global food and energy prices, hitting African economies. When the advanced countries increased interest rates to fight inflation, the payment burden of debt-ridden countries ballooned. In Africa, Zambia and Ghana defaulted on their payments, and then reached agreements with their creditors to restructure debt. Mr. Ruto, who came to power in 2022, has promised to address the debt problem. But he has been unimaginative and conventional, letting the unpopular IMF dictate one-sided policy measures. Now that the Bill has been withdrawn, he will have to tread carefully. He has yet to spell out his next measures, besides saying that austerity measures would be rolled out. He will have to strike a balance between his people’s needs and Kenya’s creditors. Multinational and bilateral lenders should help the debt-laden countries in Africa come out of this trap without punishing their poor populace.