WHO reports shows India has plugged gaps in TB care. Funding deficits could delay eradication

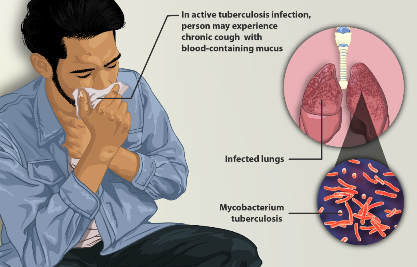

The World Health Organisation’s (WHO) latest report on the global tuberculosis burden lists positives for India. The report acknowledges the progress made by the country in closing the gap between detected and undiagnosed cases in the past eight years. In 2023, India was estimated to have had 27 lakh TB cases, of which 25.1 lakh patients were receiving medication. The fact that more than 85 per cent of those suspected to have contracted the bacterial infection were under treatment is significant given the disease’s virulence — more than 50 per cent of those who don’t fall under the medical system’s radar succumb to the infection. The report also lists successes in containing multi-drug resistant TB, signaling the efficacy of some of the recent interventions of the government — shortening the treatment period, for instance.

WHO data shows that India registered an 18 per cent decline in TB incidence in the past eight years. This is more than double the pace of decline compared to the global decline of 8 per cent, the premier health agency suggests. However, at this pace, the country will find it difficult to realise its target of eradicating the disease by 2025. Despite the government’s commitment, challenges such as insufficient awareness, inadequate medical facilities and under-nutrition continue to dog the TB elimination programme. Last year, a Lancet report pointed out that poor diet in adults contributes to 35 to 45 per cent of all new cases annually, while undernutrition in patients with TB is a major risk factor for mortality. The government does have a scheme for nutritional support for patients of the bacterial disease. Though the percentage of TB patients covered under the programme has increased appreciably in the past six decades, experts say that the amount is too less to adequately benefit the economically disadvantaged. Government data also shows that support continues to elude more than a fifth of the TB infected.

A study published in PLOS Global Health last year noted that the families of a significant section of the TB-affected in India faced catastrophic costs. WHO estimates this figure to be as high as 20 per cent. The global agency flags a significant fall in funding to eradicate the disease in India — from $ 432.6 million in 2019 to $ 302.8 million in 2023. The government has been open to course correct its TB elimination programme. Given its reach, the government’s health insurance programme could be opened to TB patients, especially those with the more virulent form of the infection. That could go a long way in eradicating TB in India.