Express view on Technology vs TB.

WHO data shows India has taken impressive strides in countering tuberculosis since 2015. The number of reported cases has dropped by 17 per cent and deaths have come down by more than 20 per cent. Even so, the country accounts for more than a fourth of the world’s TB burden and nearly 30 per cent of the deaths caused by the disease. India does not appear to be on course to meet its target of eliminating the disease by the end of this year. That’s why the government’s initiative to use cutting-edge technology, including AI, in its anti–TB programme is a step in the right direction.

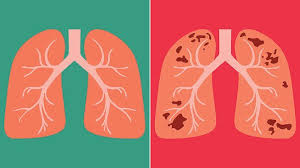

TB can be tough to detect. The traditional sputum test has major limitations, including inadequate sensitivity, poor performance in some sections of patients, especially children and people living with HIV, and inability to detect antimicrobial resistance. In 2023, the WHO recognised diagnosis as the weakest link in TB care. While the landscape of research has expanded, doctors in large parts of the Global South, including India, continue to rely on the sputum test. The anti–TB programme’s plan to widen the diagnostic net by using other samples — such as blood, saliva, or stool — is in line with the WHO’s new guideline to “invest in novel diagnostic techniques”. So is the use of genetic material to detect the bacteria. The new initiative seems to have accounted for the longstanding weakness of the Indian healthcare system — the shortage of facilities and trained professionals in rural areas. The use of AI to read microscopy slides and X–rays could be a breakthrough.

Until recently, the standard medication course took six to nine months to complete, and treatment for drug–resistant tuberculosis could take up to two years with much lower chances of cure. In the past five years, new drugs have helped reduce the length of therapy. Even then, the regimen is taxing on patients and their caregivers. The defaulting patients then run the risk of contracting the more virulent multidrug–resistant version of the disease and spreading it. A simple test can now measure compliance with the drug regimen — when a patient’s saliva is put on the strip, it can tell whether they have taken the medicine in the last 24 hours. The government would, however, be doing injustice to its initiative by relying solely on technology. State-of-the-art diagnostics should be accompanied by initiatives to improve the nutrition of patients and their access to medicines.