Cease and desist : On the Bengaluru voter data theft

The BBMP had no business outsourcing electoral work to an NGO

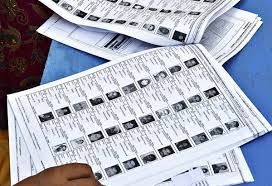

The Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike’s decision to cancel permission provided to an NGO, Chilume Educational Cultural and Rural Development Trust, to conduct a house-to-house survey to enhance voter awareness, was a belated but necessary one. BBMP, the Bengaluru civic body, has claimed that the NGO had violated the conditions, which did not allow the collection of voter identification details. It is alleged that the NGO utilised BBMP identification cards to secure voter data through a door-to-door survey and stored the data in an app created for that purpose. The NGO’s brazenness, whereby voters were deceived into believing that the collectors were with the BBMP, suggests the incompetence and the callousness of the municipal corporation of one of India’s largest cities. The data collected, such as Aadhaar, phone number and voter ID, could be easily harvested for use by parties besides constructing the meta data and profiles of potential voters. Such data are especially coveted by political parties that thrive on exclusionary politics as it allows them to target specific communities and localities with diverse demographics. If the BBMP’s purpose was to simply enhance voter awareness, there was no express need to outsource this to a non-governmental third party. The corporation must ensure that any data stored are immediately deleted and legal actions taken against the NGO.

The continued absence of a data protection law in India, and the fact that the Government’s most recent draft Bill is light on protection from the misuse of data by the state, have added to the graveness of the situation. Recently, there have been several reports of block level officers of the Election Commission of India (ECI) asking individuals to link their Aadhaar with their voter IDs, and that a failure to do so could lead to their voter IDs being cancelled. Such mandatory linking would be incorrect as it has been legally established that Indian voters can use any of the prescribed identity documents to establish their eligibility to vote. While the use of Aadhaar numbers to ascertain proof of residence makes it easier for ECI officials to verify electoral rolls and to avoid duplication of the voter id, there is also the threat of disenfranchisement of genuine voters as Aadhaar biometric authentication has been known to be less than fool proof. The ECI is better off in doing door-to-door verification and in reminding voters to check and update their voter id by accessing the websites of its respective electoral officers. Instead, the search for easy technological fixes or outsourcing is sure to result in a failure to prevent the misuse of personal information.