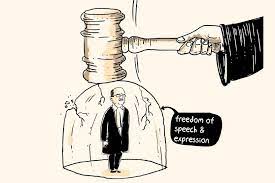

Freedom in authority: On the right to free speech

The Supreme Court is right in not adding to curbs on free speech, but leaders must value restraint

In a recent verdict, the Supreme Court has shown sound restraint while examining the issue of misuse of free speech, especially by political functionaries holding public office. It is to the credit of the Constitution Bench that it did not make any adventurous attempt to expand the scope of the restrictions already spelt out in the Constitution. The context being some rash and intemperate remarks by two ministers, one while serving in the Uttar Pradesh Cabinet and another in Kerala, there was some expectation that the court should carve out an additional restriction on public servants either by making the state vicariously liable for their remarks or by evolving a code of conduct enforceable by law. The four judges who signed off on the main opinion, as well as the fifth judge who wrote a separate one, correctly concluded that the specified grounds for reasonable restrictions in Article 19(2) are “ exhaustive ” and nothing further can be added by judicial fiat. The majority also declined to expand the notion of ‘collective responsibility’ to fix liability on the state for such remarks. Justice B.V. Nagarathna, writing a separate opinion, differed on this point, saying it is possible to attribute vicarious responsibility to the government if a minister’s view represents that of the government and is related to the affairs of the state. While the issue is largely academic, there have indeed been instances of courts taking note of individual ministers’ public remarks to transfer sensitive investigations to other agencies based on an apprehension of injustice if a police probe remained with the State concerned. Political leaders do need an occasional reminder that they should show utmost restraint, as their public utterances tend to get circulated and also influence their followers.

In the course of the discussion, the court has restated and clarified several principles, including that of constitutional tort, or a civil wrong that is actionable. The main opinion concludes that a mere statement by a minister that goes against an individual’s fundamental rights may not be actionable, but becomes actionable if it results in actual harm or loss. Justice Nagarathna, on the other hand, holds the view that there should be a proper legal framework to define acts and omissions that amount to ‘constitutional tort’. The court’s overall view that fundamental rights are enforceable even against private actors is indeed a welcome one. This largely settles the question of whether these rights are only ‘ vertical ’, that is, enforceable only against the state, or ‘ horizontal ’ too, that is enforceable by one person against another