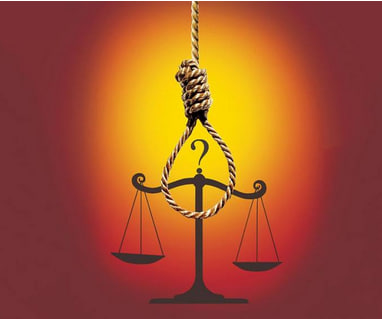

Abolition is the way: On the higher judiciary’s move on the death penalty

The issue is the death penalty itself, not merely the method of execution

Forty years after holding that the mode of executing prisoners by hanging cannot be termed too cruel or barbaric , the Supreme Court of India has now ventured to find out if there is a more dignified and less painful method to carry-out death sentences . The idea of finding an alternative mode of execution, one considered less painful and involves little cruelty , has been part of the wider debate on whether the death penalty should be abolished . Judicial and administrative thinking have leaned towards backing both the idea of capital punishment and the practice of hanging. The Bench has sought fresh data to substantiate the argument that a more humane means of execution can be found. There are two leading judgments on the issue — Bachan Singh vs State of Punjab (1980), which upheld the death penalty, but limited it to the ‘rarest of rare cases’, and Deena Dayal vs Union of India And Others (1983), which upheld the method by ruling that hanging is “as painless as possible” and “causes no greater pain than any other known method”. The 35th Report of the Law Commission (1967) had noted that while electrocution , use of a gas chamber and lethal injection were considered by some to be less painful, it was not in a position to come to a conclusion . It refrained from recommending any change.

Even though the Supreme Court has not favoured abolition, it has developed a robust and humane jurisprudence that has made it difficult for the executive to carry out death sentences. It has restricted its use to the ‘rarest of rare cases’, mandated a balancing of aggravating and mitigating circumstances before sending someone to the gallows , and allowed a post-appeal review hearing in open court. At the same time, it has evolved a clemency jurisprudence that makes decisions on Mercy petitions justiciable and penalises undue delay in disposing of mercy pleas by commuting death sentences to life. The question now before the Court provides yet another opportunity to humanise its approach further. Empirical evidence suggests that hanging need not result in an early or painful death, while there is a body of proof that shows electrocution and lethal injection have their own forms of cruelty. The Union government contends that hanging should be retained, not only because it is not cruel or inhuman but also because it accounts for the least number of botched-up executions. The real issue, however, is that any form of execution is a fall from humaneness , offends human dignity and perpetrates cruelty. Debating the mode only deepens the moral dilemma of whether the taking of life is the best response to the taking of life. If eliminating cruelty and indignity is the aim, abolition is the answer.